| « “Chapter 8: Argentina” | “A Resurgent MERCOSUR: Confronting Economic Crises and Negotiating Trade Agreements” » |

“Economic Integration as a Means for Promoting Regional Political Stability: Lessons from the European Union and MERCOSUR”

Volume 80, No. 1; Chicago Kent Law Review (2005) pp. 187-213.

Introduction

The cataclysmic breakup of the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia during the 1990’s resulted in the creation of at least five new countries and a protectorate administered by the United Nations. Even the loose federation established in February 2003 between Montenegro and Serbia may yet lead to full Montenegrin independence. The small internal markets of many of these new countries, several of which have their own separate, and often non-convertible currencies, gives rise to concerns about their future viability as stable economic and political entities. Membership in the EU provides one solution to this dilemma, but other than Slovenia, which joined in May 2004, and Croatia,1 accession by the others appears remote at the present time. Accordingly, regional economic integration provides another, more immediate alternative by offering the prospects of economies of scale for local producers, and the reestablishment of broken chains of production as well as the creation of new ones so as to enhance export competitiveness. In addition, an economically integrated Balkans enhances the region’s ability to attract much needed foreign direct investment.

Although the widespread atrocities directed against civilian populations are still fresh in the memories of many living within the territory of the former Yugoslavia, the desperate need to encourage economic growth and create new jobs provides an important incentive for more pragmatically oriented democratic leaders to overlook past wounds and promote regional economic integration. By including countries such as Albania, Bulgaria and Romania, which were not directly involved in the recent bloodshed, the project’s political viability is enhanced. An economically integrated Balkans may also facilitate eventual accession by all the participating states into the EU by providing solutions to at least some of the problems that, if not adequately redressed, can only impede their membership indefinitely.

Perhaps most importantly, promoting an effective project to economically integrate the countries of the Balkans offers a more a realistic way to resolve Kosovo’s current limbo status as a de facto independent entity that is formally under Serb sovereignty yet administered by the U.N. If the example of the EU is taken as a model, a fully functioning Balkans economic union would mean greater economic and political autonomy for Kosovo regardless if, under international law, it technically remained under Serb sovereignty (albeit in the form of a loose confederation). Even if the option of full independence is pursued, an economically integrated Balkans enhances Kosovo’s ability to prosper. An integrated Balkans also allows Kosovo to stand on its own feet economically without incorporation into a Greater Albania, whose creation could well plunge the Balkans into renewed conflict.

This paper examines the experiences of the EU and MERCOSUR integration projects that have led to permanent peaceful relations among the participating countries and contributed to overcoming historically bitter rivalries and conflicts. In particular, the paper attempts to focus on lessons that can be gleaned from these two economic integration projects that may be relevant for any effort to integrate the Balkan countries (including, perhaps, the eventual establishment of some form of political union). Examining the EU experience with regionalism is especially relevant to any discussion of Kosovo’s final status, because it may provide a pertinent model for ensuring Kosovo’s future economic viability and territorial and cultural integrity, thereby avoiding the outbreak of another war in the Balkans.

I. The Origins of the European Union as a Response to the Carnage of WW II and Its Ultimate Goal of Political Union

The idea of a formal political union in Europe flourished in the waning days of the Second World War and in the immediate post-war period. Historian Anthony Sutcliffe relays that:

In Italy, many of the imprisoned opponents of Mussolini developed a case for a Federal Europe following the conclusion of the war as the only way to prevent future conflicts. In 1944, the European Resistance movements, of which the French was the largest and the most successful, met in Geneva where they drafted a declaration calling for a Federal Europe after the war.2

The main advocate for political union was the European Union of Federalists, an organization founded in 1943.3

Sutcliffe continues:

[A]t a conference of the main European federalist organizations at The Hague in May 1948, a proposal for a European Parliament was rejected in favour of the idea of the Council of Europe, with a Council of Ministers and a Consultative Assembly nominated by the national governments. This weak, consultative body, which was largely the result of British objections to the loss of sovereign power [that a European Parliament presumably entailed], was set up at Strasbourg in 1949. This modest result was a disappointment for the federalists, who never again reached the same degree of influence with European governments. From now on, the locus of European integration switched to the economic and military [sectors].4

This does not mean, however, that the vision of eventual political union was abandoned. It is just that more pragmatic advocates of a Federal Europe, such as Jean Monnet of France, recognized that by first focusing on the establishment of economic links, even if limited in their scope, this could generate broader cooperation in the long run.5

Interestingly, from June 1948 onwards the operation of Marshall aid became an important pillar supporting efforts at western European economic integration.6 In 1949, the Economic Cooperation Administration (which oversaw implementation of the Marshall Plan) adopted economic integration in Europe as a central policy.7 In order to facilitate intra-regional trade, the European Payments Union was founded as a central clearing house mechanism on July 1, 1950 to overcome previous problems associated with restrictive national monetary exchange controls.8

On May 9, 1950 then French Foreign Minister Robert Schuman, proposed the integration of coal and steel production in Europe under the control of a “common high authority”.9 The coal and steel plan, which included the creation of a body with supranational authority, was deemed by its French proponents as a route towards European cooperation on a broader scale.10 The plan sought to integrate the production and exchange of iron and steel products between Germany and France, and such other producer countries as might wish to join. Germany, France, Italy, and the three Benelux countries agreed to discuss the plan.11 The basic thrust of the plan, as understood by all the members, was to overcome traditional French-German enmity by closely linking sectors historically identified as underpinning the war machine.12

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was formally established in August 1952 on the basis of the Treaty of Paris, which had been signed in April 1951.13 The economic success of the ECSC, which had a partial Common External Tariff (CET), suggested that a broader customs union might be the ideal vehicle for achieving European integration.14 Equally as important, the ECSC began the process of liberating France from a “counterproductive desire to find security through strategies of dismemberment and the restriction of German production.”15

In late 1954, the six governments that made up the ECSC began to consider a new economic initiative that would complement their original coal and steel pact.16 These discussions eventually led to the March 1957 signing of the Treaties of Rome instituting Euratom (i.e., the European Atomic Energy Commission) and the European Economic Community (EEC).17 The latter sought to establish a customs union among the initial six participating states, develop common policies on transport and agriculture, prohibit monopolies, and assist less well-off regions through a Social Fund and Investment Bank.18 The creators of the Treaties of Rome were not, however, primarily motivated in establishing an economic union.19 Instead, they saw economic integration as a step towards political union, the hope being that political unity would eventually evolve out of closer economic cooperation.20

The end of military dictatorships in Greece, Portugal, and Spain during the 1970’s opened the way for Greek accession into the EEC in 1981, followed by Portugal and Spain in 1986.21 Because democracy was a prerequisite for membership, accession into the EEC was viewed by the Greek, Portuguese and Spanish governments as a means of guaranteeing the preservation of their democratic institutions.22

II. The Growing Importance of the Regions within the European Union

Regarding regionalism, Sonia Mazey writes:

[A]lthough not officially recognized as partners in the founding treaties of the European Community, regional authorities throughout the [EU] have, since the early 1980’s, become increasingly involved in [first the EEC and now EU] policy process. This change has been accompanied by the emergence of an increasingly assertive “regional lobby” in Brussels and growing support for a “Europe of the regions”.23

Part of the explanation for this development can be traced to the ratification of the 1992 Treaty of Maastricht and its underlying general principle of “subsidiarity”.24 Federalists have used subsidiarity to argue not only for more Community action but also for greater participation by the regions of member states in EU rulemaking.25 “In short, European integration has prompted the emergence of new regional groupings, networks and processes which transcend the territorial and legal parameters of ‘old’ regions defined by the nation-state.26

The increasing importance given to regional authorities by the EU in terms of formulating and implementing overall policy and legislation helps to explain another interesting phenomenon. Among the biggest supporters of the EU are ethnic groups or inhabitants of nations long subsumed into larger states but still resentful of central rule from that country’s capital. With Brussels increasingly the locus of rulemaking power and The increasing importance given to regional authorities by the EU in terms of formulating and implementing overall policy and legislation helps to explain another interesting phenomenon. Among the biggest supporters of the EU are ethnic groups or inhabitants of nations long subsumed into larger states but still resentful of central rule from that country’s capital. With Brussels increasingly the locus of rulemaking power and a source of generous economic aid (coupled with monetary policy being set for most by the European Central Bank in Frankfurt), the traditional stranglehold exerted by central governments on regional cultural and economic development has diminished.27 Accordingly, this phenomenon allows regions to peacefully “break out” of their nation-states without necessarily suffering any economic penalty or risking bloodshed. For example, an increased voice for Catalonia in the EU makes demands for independence from Spain unnecessary. Similarly, increased representation for Flanders in the EU under the auspices of the Belgian government has diminished separatist sentiment. On the other hand, Scottish nationalists use the idea of Scotland’s European vocation as a way of counteracting the fear that independence might lead to isolation or poverty.28 According to this view, the 1997 devolution of certain lawmaking functions from London to Edinburgh and eventual independence for Scotland “are of a piece with the creation of a federal Europe.”29 A powerful counterargument to this scenario, however, posits that devolution and the creation of a Federal Europe actually undermines the appeal of any separatist movement in Scotland by making full independence wholly unnecessary and even redundant.30

III. An Historic Overview of Relations Between Brazil and its Spanish-Speaking Neighbors in the River Plate Basin

During much of the colonial period, the River Plate Basin of South America was at the front line of the competing imperial interests of Spain and Portugal. Each nation sought to control the mouth of the River Plate and access to an extensive mule and waterway system that penetrated into the interior of the South American continent.31 As part of that struggle, the territory of what is today Uruguay passed from Spanish to Portuguese hands and vice versa several times from the seventeenth through the early nineteenth centuries.32 For its part, Paraguay and its Jesuit Missions were the target of numerous incursions from Portuguese slave raiders and fortune seekers, called bandeirantes, which were based in southern Brazil.33

Formal independence from Spain in 1816 of the United Provinces of the River Plate (which technically included Paraguay and Uruguay and what is today the Argentine Republic) did not end the territorial disputes in the region as the new Brazilian Empire (itself an outgrowth of the Portuguese royal family’s forced sojourn in Rio de Janeiro during the Napoleonic conquest of the Iberian peninsula) eventually annexed Uruguay in 1820.34 In 1825, the Uruguayans rebelled against their Brazilian overlords and sought to reestablish a federation with Argentina.35 The matter of who controlled Uruguay was finally settled in 1828 when the British, fearful that renewed warfare between Argentina and Brazil would severely disrupt their lucrative trade activities in the region, intervened as mediators.36 The result was the creation of an independent Eastern Republic of Uruguay.37

Peace in the River Plate region was again interrupted in 1864 as a result of the War of the Triple Alliance. Alarmed by what he perceived to be Argentine and Brazilian interference in the internal affairs of Uruguay (and a possible attempt by both to dismember the country), then Paraguayan strongman Francisco Solano López issued strident declarations throughout 1864 in support of the embattled Blanco Party President in Montevideo.38 When the Brazilians actually invaded Uruguay in September of 1864, Paraguay sent troops to capture the interior Brazilian province of Mato Grosso and seized a Brazilian river boat (whose passengers included the governor of Mato Grosso) passing through its territory.39 In March of 1865 Paraguay formally declared war on Argentina when Buenos Aires refused Solano Lopez’s request to transit through Argentine territory in order to attack southern Brazil.40 This declaration of war was followed weeks later by Paraguay’s capture of the important Argentine river port city of Corrientes.41 Argentina finally responded in May of 1865 by entering into a Triple Alliance with Brazil and the new Colorado Party government in Uruguay (the successor to the embattled Blanco regime that was finally overthrown with Argentine and Brazilian assistance in February 1865) against what was now viewed as a dangerously belligerent Paraguayan dictator.42 The results of the war that finally ended in 1870 were catastrophic for Paraguay.43 Parts of the country were annexed by Argentina and Brazil, and most able-bodied Paraguayan men had been killed.44

Despite their alliance in the war against Paraguay, Argentine-Brazilian relations soon frayed in a dispute over who should head the new post-war government in Paraguay.45 Historian Stanley Hilton relays that:

During [the period of the Brazilian] “Old Republic” (1889-1930), Brazil observers carefully studied Argentina’s commercial and political efforts in the [River Plate Basin] and concluded that, in a drive for continental supremacy, [Argentina] was seeking to isolate Brazil…by establishing a modern version of the Vice-Royalty of La Plata, the Spanish colonial administrative unit that had included [modern day] Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Bolivia. Turn-of-the century naval purchases [by Argentina], followed by a World War I [military] build-up and unprecedented [Argentine] defense budgets in the 1920’s generated deep anxiety in [Brazil], where the possibility of war between the two countries was a permanent theme of strategic discussion.46

World War II exacerbated tensions in Argentine-Brazilian relations, as Argentina initially remained neutral and became decidedly more sympathetic to the Axis cause following a military coup in 1943.47 By contrast, Brazil sided with the Allies and even sent troops to fight in Italy alongside the Americans.48 During this period, the Brazilians feared that Buenos Aires might launch an attack in coordination with potential fifth columnists recruited among southern Brazil’s large population of persons of Italian and German descent.49

At the conclusion of WWII, Argentina found itself with a deteriorating economy while Brazil, in contrast, was booming.50 The tax revenues generated by sales of higher priced coffee were channeled into continued expansion of Brazil's industrial sector.51 In addition, Brazil used its participation in WW II on the Allied side to get the United States to fund the development of Latin America’s largest and only fully integrated steel making factory at Volta Redonda.52 Realizing the bind his country was in, Argentine President Juan Domingo Peron felt compelled to seek closer economic ties with the other South American republics.53

In 1948 Argentina and Brazil signed an agreement in which each country agreed to use the Brazilian cruzeiro as the common currency in their bilateral trade, favor each others’ shipping lines, and set up a commission to investigate constructing a hydroelectric dam at Iguaçu from which Argentina could harness electric power.54 Peron's attempts to garner closer commercial links with Brazil were hampered, however, by the great distrust most Brazilian policy makers continued to harbor against Argentina.55 Furthermore, having just emerged from their own long struggle against the dictator Getulio Vargas, Brazil’s elite did not want to be seen as undermining the Argentine liberals' struggle against Peron by entering into a close economic alliance with him.56 In the end, Peron's only concrete contribution to closer Argentine-Brazilian relations was to inaugurate the first bridge that directly linked both countries by road.57

During the administration of Brazilian President Juscelino Kubitschek (1956-60), the arguments of a newer and generally younger group of foreign policy technocrats in Brazil prevailed, namely that an entente with Argentina was necessary to enhance Latin America's international bargaining power.58 Brazil's new willingness to deal with Argentina, however, would have to wait until the civilian government in Argentina of Arturo Frondizi (1958-62) in order to pay dividends.59 Facing a growing balance of payments crisis induced by the end of the Korean War, Frondizi turned to Argentina's continental neighbors to expand exports and thereby boost the country’s foreign reserves. This need led to the formation of the Latin American Free Trade Area or ALALC in 1960, an organization whose concept Kubitschek had also earlier championed.60

In April of 1961, then Presidents Frondizi of Argentina and Janio Quadros of Brazil (1960-61) met in the Brazilian border town of Uruguaiana to discuss their mutual trade problems vis-à-vis the United States and to spur an equitable increase in Argentine-Brazilian bilateral trade.61 Both presidents agreed that for the latter to occur, Argentina and Brazil would have to overcome their traditional military rivalry and cooperate on economic development matters.62 Unfortunately the two agreements signed at Uruguaiana calling for, inter alia, increased legal, economic, financial and cultural integration and the free movement of persons between Argentina and Brazil were never fully implemented.63 Quadros resigned shortly after signing them and his successor, João Goulart, was absorbed in fighting off domestic political threats that eventually led to his overthrow by the Armed Forces in 1964.64 Frondizi, for his part, was overthrown in a military coup d'état in 1962.65

The strong anticommunism of the new Argentine and Brazilian military rulers that overthrew Frondizi and Goulart, respectively, initially united Argentina and Brazil in the mid-1960s in a crusade against a perceived common enemy, Communism.66 A proposal by the Argentine government headed by General Juan Carlos Ongania (1966-69) to Brazilian President General Humberto de Alencar Castello Branco (1964-67) to establish a common market between the two countries floundered, however, as a result of opposition from Argentine industrialists who feared that it would turn Argentina into an exclusive purveyor of agro-industrial goods.67 In addition, there was little interest in the proposal on the part of Brazilian businessmen, who were more interested in servicing their rapidly growing internal market that was heavily protected from foreign competition by high tariff barriers.68

On April 26, 1973, Paraguay and Brazil signed the Treaty of Itaipú that allowed Brazil to build a major hydroelectric dam near Iguaçu Falls on the Paraná River separating the two countries.69 Argentina strongly opposed the Itaipú project, arguing that it would impede river currents flowing into its territory and undermine Argentine plans to build two hydroelectric stations further downstream.70 The Argentines also feared that construction of the Itaipú dam was a Brazilian attempt to create a new economic pole that would further isolate undeveloped and sparsely populated Misiones province from Buenos Aires.71 Despite the death knell it spelled for efforts at regional economic and political cooperation, Brazil refused to be dissuaded and embarked on construction of the Itaipú dam.72

While Argentina's economy continued to stagnate throughout the early 1970’s, Brazil experienced double digit growth rates in GDP. Brazil's new found economic strength also contributed to its taking on the role of a regional hegemon, intervening in the internal affairs of its neighbors so as to prevent leftist ideas and instability from seeping into Brazil and threatening the country’s economic miracle.73 These Brazilian interventions added fuel to a growing perception in Spanish America that Brazil was a "key country" or "privileged satellite" of United States imperialism in the region.74

As the 1970’s drew to a close, Brazil’s military leaders came to the conclusion that the country’s national development could not be achieved separate from the Latin American context.75 As a way of more fully reincorporating itself into the Latin American political community, in 1978 Brazil signed, along with Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana and Surinam, the Amazonic Cooperation Treaty.76 Shortly thereafter, Brazil began making overtures to the Andean Pact countries and promised to contribute to their regional development programs and to increase imports from them.77

Brazil took the first important step of mending fences with Argentina when it signed a Tripartite Agreement with Argentina and Paraguay on October 19, 1979, which ended the controversy over the Itaipú dam.78 This move coincided with Argentina's own desire to resolve any problems it may have had with Brazil as a result of the deepening of Buenos Aires’s dispute with Chile in the Beagle Channel and an awareness of the Chileans traditional close diplomatic ties with Brazil.79 If war were to break out with Chile, Argentina was anxious to avoid the formation of a second front on its northern border.80

III. The 1980’s Rapprochement Between Argentina and Brazil

Between May 14 and May 17, 1980, then Brazilian President General João Bautista Figueiredo visited Buenos Aires at the invitation of his Argentine counterpart, General Jorge Videla. While in Argentina, Figueiredo signed some 15 agreements that pledged closer Argentine-Brazilian cooperation in the nuclear energy field, electricity, taxation, scientific and technological research, and health.81 It was also announced that a bilateral commission would be created to study ways of economically integrating the two countries.82 Undoubtedly, the most important of the agreements signed by Videla and Figueiredo was the one calling for technological cooperation in the production of nuclear reactors and components, bilateral trade in nuclear material, joint research efforts in uranium processing, and a common position with respect to the international community.83 In signing these accords, Argentina and Brazil effectively ended a rumored nuclear arms race that had commenced between them in the early 1970s and threatened to destabilize the whole continent.

Further efforts at closer economic integration between Argentina and Brazil during the early 1980’s were stymied by fact that the Argentine economic team, headed by José Martinez de Hoz, was forced to resign in 1981. Another important factor was the inauguration of a new, conservative administration in Washington, D.C. in January 1981 that led Argentina's military leaders to temporarily favor closer political and economic ties with the United States over those with Brazil.84 Whatever illusions the Argentine military may have had regarding the benefits closer U.S. ties would bring them were quickly shattered when the Reagan administration backed Britain in the Malvinas dispute in 1982. That betrayal forced the Argentine military government to look for diplomatic support in Latin America as part of the country’s effort to recover the islands, including support from traditional rival Brazil.

The 1982 Argentine defeat by the British in the South Atlantic generated considerable introspection in Argentina and caused the Brazilian military to rethink their premises about Argentina as a serious military threat or a country likely to engage in any future military adventures.85 As a result of the Malvinas fiasco, a new concept of national security began to emerge in both Argentina and Brazil, one based on socio-economic factors as opposed to traditional national defense strategies.86 Accordingly, by the mid-1980’s, neither Argentina nor Brazil viewed the other as reciprocal threats but instead saw each other as necessary partners whose mutual cooperation was needed in order to overcome the serious problems both countries were facing with respect to world trade and the international banking community.87

During a ceremony in November of 1985 to inaugurate a new bridge near Iguaçu Falls connecting Argentina with Brazil, then Argentine President Raul Alfonsin (1983-1989) and Brazilian President José Sarney (1984-1990) agreed to establish a binational commission to review the possibilities for greater bilateral economic cooperation and integration. The recommendations of that binational commission led to the Argentine-Brazilian Program for Integration and Economic Cooperation (better known by its Spanish and Portuguese acronym (“PICAB”)) on July 29, 1986.88 The original PICAB included 12 Protocols that, among other things, liberalized bilateral trade in capital goods, wheat, and consumer products.89 On December 10, 1986, Alfonsin and Sarney signed the Act of Brazilian-Argentine Friendship in Brasilia that added an additional five Protocols to the PICAB and was accompanied by a declaration committing both countries to mutual cooperation in nuclear research and the peaceful use of nuclear energy.90 Subsequent protocols created an important bilateral managed trade regime for the automotive sector that remained in effect until 2002.91

Through the PICAB, Argentina and Brazil both hoped to accomplish a number of objectives. Perhaps one of the most important was to spark internal economic growth and thereby create domestic political stability by increasing each country’s trade with the other in a complementary fashion.92 Another major objective was to strengthen Argentine and Brazilian bargaining power with the outside world, particularly in the GATT Uruguay Round, so as to obtain more access to the heavily protected agricultural markets of the US and Europe.93 An underlying goal implicit in the PICAB, as evidenced by specific Protocols dealing with the nuclear sector, was to strengthen Argentine-Brazilian relations in such a way that it would render the traditional military hypothesis of inevitable conflict between both countries permanently obsolete.

In November of 1998, Presidents Alfonsin and Sarney met in Buenos Aires to sign a Treaty of Integration and Economic Cooperation (which came into effect the following year after it was ratified unanimously in both the Argentine and Brazilian Congresses).94 The Treaty committed both countries to begin taking steps that would gradually culminate in an Argentine-Brazilian common market by 1999.95 Although both countries were wracked by severe economic crises at the time, forging closer Argentine-Brazilian economic links made good political sense because the PICAB was one of the few policy initiatives that had produced any positive results.96

In order to demonstrate just how close Argentine-Brazilian relations had become as a result of the PICAB, President Sarney visited a top secret Argentine nuclear research station in Ezeiza following the signing ceremony for the Treaty of Integration and Economic Cooperation.97 Further evidence was provided by the fact that the Argentine and the Brazilian armies no longer used the other country as a potential enemy when conducting war games.98 As a result of these mutual changes in attitude, Presidents Alfonsin and Sarney were able to sign Protocol 23 to the PICAB in November 1988, thereby permitting factories to be built along their respective common borders.99 Prior to this time, traditional national security concerns in both countries had dictated that development be directed at a safe distance from the Argentine-Brazilian border and potential enemy artillery. These traditional military concerns also explained why, prior to the 1990’s, Argentine roads and bridges near the Brazilian border were purposely constructed so as not to withstand the weight of an invading Brazilian tank and neither country utilized the same railroad gauge.

V. How the Appearance of MERCOSUR Has Permanently Transformed the Political Landscape of South America’s Southern Cone

On July 6, 1990, then Argentine President Carlos Menem (1989-99) and Brazilian President Fernando Collor de Mello (1990-92) signed the Act of Buenos Aires.100 The Act called for the creation of an Argentine-Brazilian common market by 1995, instead of the 1999 date targeted by both their predecessors.101 The actual rules for eliminating duties and non-tariff barriers between Argentina and Brazil were set down in Latin American Integration Association (“ALADI”)102 Economic Complementation Agreement No. 14 that came into effect on January 1, 1991. Fearful of losing access to their largest export markets, Paraguay and Uruguay petitioned to be included in this proposed Argentine-Brazilian common market.103 The result was the Treaty of Asuncion signed by Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay on March 26, 1991 (and incorporated into the ALADI framework as Economic Complementation Agreement No. 18).104 The Treaty of Asuncion was ratified by the legislative powers in all four countries on unanimous votes (except in Uruguay, where only two congressmen voted against the proposal).105

The Treaty of Asuncion sought to have a free trade area in place among all four countries and a Common External Tariff (“CET”) established for goods imported from the outside world by 1995.106 In actuality, the free trade area took some years longer to fully implement than originally contemplated, but today only sugar is still excluded from intra-regional free trade.107 Similarly, while a CET was established by January 1, 1995, it only applied to about 85 percent of the tariff lines found on MERCOSUR’s harmonized tariff schedule.108 Subsequent economic crises and preferential trade arrangements, not encompassing all four countries, created additional perforations to the CET.109 It is now expected that MERCOSUR’s CET will not be fully operational until 2010.110

As tariffs among the MERCOSUR countries were gradually eliminated throughout the 1990’s, intra-regional trade exploded, nearly quadrupling to U.S.$ 20 billion by 1998 over the level recorded in 1990.111 Interestingly, this dramatic growth in intra-MERCOSUR trade also came at a time when MERCOSUR’s exports to the rest of the world were also increasing.112 Subsequent economic crises, beginning with the maxi-devaluation of the Brazilian real in January 1999, wreaked havoc on intra-MERCOSUR trade flows (including a significant contraction in 2002).113 Despite these setbacks, none of the MERCOSUR governments has reversed course and abandoned the integration process.114 Following his landslide victory in the October 2002 election and before he was even inaugurated, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva visited Argentina and Chile to underscore the importance he attached to MERCOSUR as a means of restoring economic growth and stability to the region.115 Joining him in that vision was Nestor Kirchner, who became President of Argentina in May 2003, and Nicanor Duarte Frutos, who assumed the Paraguayan presidency on August 15, 2003.116

Today, MERCOSUR is a political and economic reality that, among other things, supports democracy in South America’s Southern Cone. For example, in 1996 the MERCOSUR governments prevented a military coup d’etat in Paraguay by making clear to the plotters that the overthrow of then President Juan Carlos Wasmosy would mean the immediate suspension of Paraguay’s membership in the MERCOSUR.117 This was followed in July 1998 by the signing of the Protocol of Ushuaia by the presidents of all four core MERCOSUR countries plus associate members Bolivia and Chile.118 The Protocol outlines a series of procedures to follow in the event of a break in the democratic order in any of the signatory states.119

MERCOSUR has also served as a catalyst for hundreds of cross-border investments within the sub-region, a phenomenon virtually unknown prior to the 1990’s and necessary to create internationally competitive sub-regional firms.120 Furthermore, MERCOSUR has widened the scope and deepened the level of intra-regional relations through “[r]egional infrastructure initiatives, cooperative agendas in education and culture, and heightened interaction among political actors of [the] member states.121

More recently, MERCOSUR has proven itself an effective counterweight to U.S. special interest groups that are trying to whittle down the originally ambitious agenda to create a genuine Free Trade Area of the Americas (“FTAA”) that encompasses thirty-four countries. This is because the MERCOSUR countries as a bloc have refused to open up their lucrative services sector or government procurement opportunities to U.S. firms until the U.S. makes meaningful concessions on reducing agricultural subsidy programs and reforming its abusive anti-dumping laws. Because there are more U.S. businesses that would profit from unlimited access to the MERCOSUR market than benefit from agricultural subsidies or the protection afforded by anti-dumping duties, the MERCOSUR bloc’s strategy has increased the pressure on the White House to cede on these issues in order to secure an FTAA. The existence of MERCOSUR has also facilitated talks to create a trans-Atlantic free trade area between the European Union and South America’s Southern Cone by reducing the number of separate offers that have to be considered during the negotiations.

IV. Is An Economically Integrated Balkans Feasible?

The idea of economically integrating the Balkans through the creation of a free trade area or customs union or an even more ambitious economic union is neither far fetched nor an historical anomaly.122 Balkan federation schemes, which consisted of various combinations among Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Romania, Turkey and Yugoslavia, were hatched following WW II.123 “The most important of the many Balkan plans was a Bulgarian-Yugoslav scheme that, in some of its versions, also envisaged the ‘integration’ of Albania.”124 An agreement signed by Yugoslavia and Bulgaria at Bled in August 1947 included reference to preparations for a customs union and, according to some participants, even discussed political federation.125 None of these schemes ever prospered as they were nixed by Josef Stalin and Yugoslavia was eventually expelled from the COMINFORM in late June 1948, following Tito’s disagreements with Soviet leaders on how to best achieve socialism.126 Among those Eastern European countries that remained within the Soviet Bloc, however, efforts continued during the first half of the 1960’s to turn the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (“CMEA”) into a more advanced form of economic integration.127 These proposals ultimately foundered on Romanian opposition.128

The pressing need exhibited by Kosovo and most countries that formally made up Yugoslavia to expand export opportunities and create real opportunities for local entrepreneurs is underscored by the dismal economic progress they have made to date. The problem in Kosovo is further compounded by the failure to resolve its final status under international law. Accordingly, the unemployment rate in Kosovo hovers close to 70%, the average month’s pay is about U.S.$ 220.00, and there is no significant foreign direct investment.129 Widespread unemployment, limited purchasing power of the majority of the populace, and little foreign direct investment is also the rule in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Macedonia, Serbia and Montenegro.130 The economic performance of Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania has also been erratic.

In the particular case of Kosovo, resolution of its final status and the elimination of tariffs on intra-Balkan trade would create opportunities for sustained economic growth. At the same time, however, it must also be acknowledged that one thing that could undermine any effort to economically integrate the Balkans is the heavy dependence by some governments on the revenue collected from import duties. Kosovo is said to be especially dependent on revenue generated through import tariffs. Accordingly, any attempt to liberalize intra-regional trade will require temporary financial assistance for governments like Kosovo as they scramble to find new revenue streams generated from the economic growth that regional free trade will likely bring.

Ernest Haas and Philippe Schmitter, two well known neo-functionalist political theorists, have identified five conditions which give strength to the economic integration process and enhance its integrative potential.131 The first of these holds that a region is “more likely to develop a viable plan if no units [within] the proposed union present an overpowering presence in size and power vis-à-vis other units.”132 The second posits that the more pre-existing integration or mutual interdependence there is before integration, the greater the proposed union’s integrative potential.133 The third condition listed by Haas and Schmitter is “the extent to which each country exhibits a pluralistic socio-political structure.”134 The expectation is that the greater the level of democratic pluralism, the greater the project’s potential for success.135 The fourth condition is based on the degree of complementation of elite values (i.e., the opinions of political and business leaders, intellectuals, and pundits) within the proposed union.136 Finally, the level of actual or perceived external dependence can give strength to the integration process.137 In this context, it is important to examine the environment of world politics in which a regional integration process is being carried out because historically unique factors can serve as an important catalyst for initiating or furthering the process.138

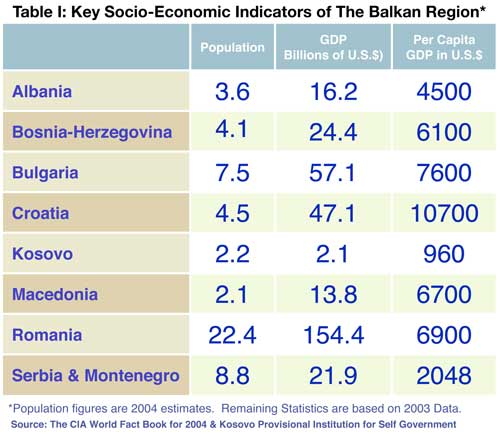

Using Haas and Schmitter’s criteria, it would appear that economically integrating the Balkans, particularly the former Republics of Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Kosovo, is viable. In terms of population and the size of their respective economies, none of the countries and territories that would make up a Balkan free trade area or other type of union overpowers the others in terms of size and power. The big exception is Romania, although the actual purchasing power of Romanians is on par with those of most fellow Balkan residents.

For Haas and Schmitter’s second condition, the economies of the former republics of Yugoslavia and Kosovo were very well integrated and mutually interdependent prior to the civil wars. For example, before Yugoslavia’s disintegration, Kosovo supplied the Yugoslav republics with colored metals and lignite coal. Kosovo also used to export electricity to Montenegro and Croatia through Serbia. This integration and mutual interdependence continues today, albeit severely diminished over previously recorded levels. Import-Export data for 2001 indicates that all the former republics count at least one or more countries that made up the old Yugoslavia (including, interestingly, Slovenia) as among their top five trading partners.139 Albania and Bulgaria also count some of the

former Yugoslav republics as their top five trading partners.140 In addition, Bulgaria contributes significantly to the Albanian import basket.141 The big exception to a high level of prior integration and mutual interdependence among the Balkan countries is Romania.142

More problematic in predicting the future viability of an economically integrated Balkans lies in fulfillment of Haas and Schmitter’s third variable. Many of the former Yugoslav republics still do not have fully pluralistic sociopolitical structures, especially when it comes to respecting the rights of certain ethnic minorities. This deficiency has also slowed their accession into the EU, which requires compliance with the so-called Copenhagen criteria of liberal democracy and respect for human rights.143 However, given that all these countries are now firmly embarked in constructing representative democracies, it does not seem implausible that they will be able to achieve fuller pluralism sometime in the near future.

A question mark also exists with respect to meeting Haas and Schmitter’s fourth condition concerning regional complementation of elite values. Although there are indications of momentum building in favor of a “Balkans without Borders”, it is still unclear just how pervasive support for such a concept is among elected leaders and other opinion makers in the region. This is particularly true in those countries (such as Bulgaria and Romania) where participating in a Balkans economic integration project might create a distraction from efforts to join the EU that are already underway.

As for Haas and Schmitter’s fifth condition, all the Balkan countries identified as candidates for the proposed Southeastern European Balkan economic integration project are highly dependent on outside capital for development and, in some cases, survive only because of foreign donor relief money and remittances from nationals living abroad.144 Accordingly, this situation facilitates integrating the Balkans, albeit not necessarily in the way foreseen by Hass and Schmitter (e.g., to reduce dependence on one dominant trading partner, etc.). Instead this high dependence can be used by foreign economic powers to steer the Balkan countries towards greater economic integration, particularly if accompanied by important carrots such as generous development aid money or as a pre-condition for joining the EU.

Although it is true that on at least two conditions (i.e., power-size homogeneity and pre-existing integration or mutual interdependency) Romania is the odd man out, the inclusion of Romania in any proposed Balkan integration scheme might be beneficial from a Kosovar perspective given that Romania’s 22.4 million mostly non-Slavic inhabitants could serve as a counterweight to the 25 or so million Slavs from the other Balkan states.145 Without the presence of the Romanians, both Albania and Kosovo (and their brethren in Macedonia) would be in the distinct minority not just on ethnic, but also on cultural and religious grounds.

Conclusion

Both the EU and MERCOSUR integration projects provide valuable lessons for any effort to economically integrate the Balkans. Perhaps the most important is that successful economic integration can be used as a way to permanently banish the specter of war and inevitable conflict among those countries participating in any such process. However, it is important to emphasize that for this to happen, the economic integration projects must also remain dynamic and offer tangible opportunities, such as increased trade flows and/or growth in cross-border investment. Just as Latin America offers MERCOSUR as a successful example of integration (especially in the political sphere) there are other Latin American projects that were unable to prevent war among their members. For example, in 1969 war broke out between Honduras and El Salvador, both members of the Central American Common Market.146 Similarly, in 1981 and again in 1995 Ecuador and Peru fought over boundary disputes in the Amazon despite both countries participation in a regional customs union. The common factor in both of these examples is that by the time armed conflicts broke out, the respective integration processes had long since stagnated and initial positive gains had even been reversed.147

Both the EU and MERCOSUR also provide evidence for the proposition that regional economic integration provides a way to strengthen weak democracies by requiring liberal democracy and respect for human rights as a condition for initial entry and continued access to the benefits provided by membership.148 Furthermore, the EU experience with subsidiarity and supranational bodies indicates that spaces can be created for long suppressed national subgroups to develop culturally and politically in a fairly autonomous fashion with minimal economic disruption or bloodshed.

From the Kosovar perspective, the exact form of economic integration any Balkans project pursues depends, to a large degree, on final determination of Kosovo’s status under international law. If full independence is pursued, a free trade area would probably make most sense since Kosovo would retain sovereignty to set its own tariff policy on non-regional imports and collect any duty revenue for its own purposes. On the other hand, opting for a loose confederation with Serbia and Montenegro might make an economic union more attractive, because Kosovo would inevitably retain important rulemaking powers over an array of subject matters that require local oversight and implementation. In addition, this deeper form of economic integration implies the existence of supranational bodies where big policy issues such as international trade relations would presumably be decided on regionally and not in Belgrade.

Whatever form of economic integration the Balkan countries adopt, this decision. in and of itself, should not impede their eventual accession into the EU. For example, the three Benelux countries were incorporated into the old EEC as an already existing customs union.149 The EU has also not been adverse to allowing large numbers of countries to join the block at one time, as evidenced by the ten new countries that became members in May 2004.150 If anything, a deeper form of Balkan integration could facilitate incorporation of the whole sub-region en masse since the EU would be dealing with an already established and cohesive economic unit and would need to make only one tariff offer to the whole block and not to several countries. This is one important lesson from the current negotiations to create a EU-MERCOSUR free trade area, where it is the EU as much as MERCOSUR that wants to negotiate bloc to bloc.151 In addition, the carrot of EU accession provides an important incentive to prevent backsliding on strengthening representative democracy, respect for human rights, and economic reform.

*The author is President of Washington, D.C. based Mercosur Consulting Group, Ltd. [http://www.mercosurconsulting.net] and teaches courses on Western Hemisphere economic integration at The George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs and Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies.

1 See, e.g., A Club in Need of a New Vision, ECONOMIST, May 1, 2004, at 25-27.

2 ANTHONY SUTCLIFFE, AN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY OF WESTERN EUROPE SINCE 1945, at 106 (1996). The joint declaration described federation as “the only means of European survival and the only method through which Germany could rejoin the European family.’ See HANS A. SCHMIDT, THE PATH TO EUROPEAN UNION 16 (1962).

3 Sutcliffe, supra note 2, at 106.

4 Id. at 107. British opposition is ironic given that “[i]n June 1940, the British government, eager to keep its stricken French ally in [WW II], offered to unite Britain and France as a single state.” Id. at 102-03. “This unusual, not to say desperate, offer was the brainchild of a French diplomat, and former businessman, Jean Monnet.” Id. at 103. Also, “Winston Churchill had been a warm supporter of the political approach to European integration.” Id. at 110.

5 Id.

6 Id. at 108. Already in January 1947, then US Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, had made an important speech before the National Association of Publishers in New York entitled “Europe must federate or perish”. Id. at 107. This support marked a remarkable shift in opinion given that during the Second World War the prevailing wisdom in Washington, D.C., seemed to be that a post-war “European union was not especially desirable from the American point of view” because it might, inter alia, injure American trade. SCHMITT, supra note 2, at 13.

7 SUTCLIFFE, supra note 2, at 108-09. Until the idea was rejected by the British, the United States also initially advocated the creation of a strong supranational body to oversee implementation of the Marshall aid program. THE ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENT OF EUROPEAN INTEGRATION 35 (Peter M.R. Stirk & David Weigall eds., 1999) [hereinafter Stirk & Weigall]

8 SCHMITT, supra note 2, at 25. Schmidt describes:

To the deficit or surplus which any of [the 16 countries that made up the Organization for

European Economic Cooperation (OEEC)] might have acquired in a bilateral [trade] partnership,

would be added the balances, negative or positive, with the remaining OEEC associates. If the

final sum showed a surplus, the Union would be the debtor. If the reverse turned out to be the

case, the country in question would owe the Union.

9 SUTCLIFFE, supra note 2, at 110. The intellectual author of the proposed European Coal and Steel Community was Jean Monnet who, as previously noted, was the French Minister who proposed to Churchill the union of France and Great Union on the eve of WWII. Id. see also note 4.

10 SUTCLIFFE, supra note 2, at 111. “Integration entrusted to a [supranational body] independent of national supervision was at the heart of Monnet’s thinking….” [T]he birth and history of the Council of Europe had demonstrated to him that no government in Europe was ready to abdicate [sovereignty] in the political sphere.” SCHMITT, supra note 2, at 59. Accordingly, cooperation in the coal and steel sectors might prove a less sensitive area to experiment with the concept of supranationality without incurring immediate opposition. Id.

11 SUTCLIFFE, supra note 2, at 111.

12 Id. The basic idea was that integrating the steel industry, through the use of coal obtained in Germany’s Ruhr and the Saar valleys with iron ore from French Lorraine, would make it economically unfeasible for Germany to ever start another war. Id. at 112.

13 The underlying premise for the ECSC was that ‘[p]ermanent free trade’ could not be ‘attained without the transfer of powers to supranational authority’.” SCHMITT, supra note 2, at 88. The creation of the ECSC had the support of the United States, “which was pleased to see the establishment of effective European institutions.” SUTCLIFFE, supra note 2, at 113. No doubt, the U.S. was also won over by Monnet’s arguments that an ECSC would prevent the emergence of a monopolistic steel cartel in Europe. See, e.g., Stirk & Weigall, supra note 7, at 63.

14 Sutcliffe, supra note 1, at 116. The ECSC had a significant impact upon the provision of housing in the coal and steel regions; it helped to reduce discrimination in freight rates; and it served as the catalyst for an increase in intra-ECSC trade which far outstripped increased production and trade with other states. Stirk & Weigall, supra note 8, at 72.

15 Id. at 72.

16 Id. at 125.

17 Id. at 124.

18 Id. at 130.

19 Id. at 124.

20 See, e.g., Sutcliffe, supra note 1, at 116 and Stirk & Weigall, supra note 8, at 124. Behind the arrangements on trade there was an implicit political agenda. With the customs union and, more far reaching, the creation of common policies or the progressive coordination of national policies, the Community would produce ‘closer relations between the Member States’. Id. at 130.

21 DICK LEONARD, THE ECONOMIST: GUIDE TO THE EUROPEAN UNION 320-21 (8th ed. 2002).

22 Stirk & Weigall, supra note 7, at 249.

23 Sonia Mazey, Regional Lobbying in the New Europe, in THE REGIONS AND THE NEW EUROPE: PATTERNS IN CORE AND PERIPHERY DEVELOPMENT 78 (Martin Rhodes, ed. 1995). Undoubtedly, “[t]he [EU’s] regional policy and the associated structural funds have [also] played an important catalytic role in the development of a regional lobby.” Id. at p. 83.

24 Pursuant to Article 3b of the Treaty of Maastricht:

In areas which do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Community shall take action, in

accordance with the principle of subsidiarity, only and if in so far as the objectives of the proposed

action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States and can therefore, by reason of the

scale or effects of the proposed action, be better achieved by the Community.”

RICHARD CORBETT, THE TREATY OF MAASTRICHT FROM CONCEPTION TO RATIFICATION: A COMPREHEMSIVE REFERENCE GUIDE 388 91993). The Treaty of Maastricht, which formally brought the EU into existence in 1993, also established a Committee of the Regions as an advisory body to be consulted by the European Commission or the European Council. Id. at 424.

25 Stirk & Weigall, supra note 7, at 277. Particularly, since the 1992 single market program, regional authorities “have become increasingly subject to and responsible for implementing EU legislation.” Mazey, supra note 23, at 81. They have, therefore, “repeatedly argued that they should be involved in the formulation of European policies.” Id.

26 Id. at 80. One, however, should be cautious of how far the EU is willing to go in overtly encouraging regionalist ambitions, for fear of antagonizing powerful member governments. For example, efforts by Catalonia, Scotland, Flanders and the German Lander to have a bigger role for the regions written into the proposed EU constitution were rebuffed as a result of pressure from France and Spain. In addition, as one EU official has pointed out “it’s already a nightmare trying to secure agreement between 15 member states, and its going to get worse after enlargement to 25. It will be totally impossible if we have to deal with more powerful regional governments as well.” Europe’s Rebellious Regions, THE ECONOMIST, Nov. 15, 2003, at 51.

27 ECONOMIST, supra note 26, at 51.

28 Id. The article notes that “[v]isitors to the office of John Swinney, head of the Scottish Nationalist Party, find two flags prominently displayed, Scotland’s cross of St. Andrew and the yellow stars of the European Union. Id. The Scottish Nationalists imagine :a thriving statelet within a larger Europe.” Who Wants the Euro, and Why, ECONOMIST, May 2, 1998, at 51.

29 Who Wants the Euro, and Why, supra note 28, at 51.

30See, e.g., Devolution: The Choice for Scotland and Wales, ECONOMIST, Sept. 6, 1997, at 56-5; Devolution Can Be Salvation, ECONOMIST, Sept. 20, 1997, at 53-54.

31 See, e.g., MARK A. BURKHOLDER & LYMAN L. JOHNSON, COLONIAL LATIN AMERICA 167, 249, 268-69, 287 (3d ed. 1998).

32 Id.; see also DAVID BUSHNELL & NEILL MACAULAY, THE EMERGENCE OF LATIN AMERICA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY 123-25, 162-63 (1988).

33 BUCKHOLDER & JOHNSON, supra note 31, at 97, 124.

34 Id. at 320.

35 BUSHNELL & MACAULEY, supra note 32, at 124, 162.

36 Id. at 124-25, 163.

37 Id.

38 Id. at 252-53.

39 Id. at 253.

40 See PELHAM HORTON BOX, THE ORIGINS OF THE PARAGUAYAN WAR 263 (1967).

41 Id. at 267.

42 BUSHNELL & MACAULAY, supra note 32, at 253.

43 Id. at 256.

44 See, CHARLES J. KOLINSKI, INDEPENDENCE OR DEATH! THE STORY OF THE PARAGUAYAN WAR, 198-99 (1965).

45 See generally HARRIS GAYLORD WARREN, PARAGUAY AND THE TRIPLE ALLIANCE (1978).

46 Stanley A. Hilton, The Argentine Factor in Twentieth-Century Brazilian Foreign Policy Strategy, 100 POL. SCI. Q. 27, 28 (1985). “Divergent policies during World War I---Brazil joined the allies while Argentina remained neutral—resuscitated fears of a military confrontation, which were [subsequently] fueled in the 1920’s by diplomatic clashes, Argentine military preparations, and the volatile Chaco territorial dispute that eventually erupted into a war between Bolivia and Paraguay from 1932 until 1935. Id. at 29.

47Id. at 31. One of the leaders of the 1943 coup was Juan Domingo Peron who used his position, first as head of the National Labor Department and then at the newly created Secretariat of Labor and Social Welfare, to build a power base among the Argentine working class that would eventually allow him to run for and win the presidential elections of 1946. Peron was re-elected under less than stellar democratic conditions in 1951, and was unable to finish his second term as a result of a military coup in 1955. See generally Juan Carlos Torre & Liliana de Riz, Argentina Since 1946, in 8 THE CAMBRDGE HISTORY OF LATIN AMERICA 73 (Leslie Bethell ed., 1991).

48 Hilton, supra note 46, at 31.

49 Id.

50 LUIZ ALBERTO MONIZ BANDEIRA, O EIXO ARGENTINA-BRASIL: O PROCESSO DE INTEGRACAO DA AMÉRICA LATINA 24 (1987).

51 Id. at 34.

52 Id. at 27.

53 Id. at 24.

54 Id. At 28. Argentina was particularly interested in gaining access to some of Brazil's cheap hydroelectric power, which by 1943 supplied 82% of Brazil's energy needs, whereas 70% of Argentina's energy demands in 1947 were still met by expensive imported coal and petroleum. Id. at p. 25. Peron was also interested in establishing closer economic links with Brazil in order to access cheap Brazilian iron and steel for his planned expansion of Argentina’s heavy industry sector. Id. at 25-28.

55 Illustrative of these fears was the secret session of the Brazilian Congress called on June 10, 1947 to discuss accusations made by an influential congressman that Argentina's support for one of the two sides in the Paraguayan Civil War of the late 1940’s was nothing more than an attempt to gain control of Paraguay and then attack Brazil. Frank M. Garcia, Grip on Paraguay Charged to Peron, N.Y. TIMES, June 11, 1947, at 16.

56 MONIZ BANDEIRA, supra note 50, at 29.

57 Inaugurada Ontem o Ponte Internacional Sobre o Rio Uruguai Pelos Presidentes da Republica do Brasil e da Argentina, O ESTADO DE SÃO PAULO, May 22, 1947, at 1.

58 Hilton, supra note 46, at 39.

59 MONIZ BANDEIRA, supra note 50, at 35.

60 Id.

61 Id. at 37-38.

62 Id.

63 Id. at 38-39.

64 Id.

65 Id.

66 Id. at 41, 44, 46.

67 Id. at 41, 46-47.

68 Id. at 45. During the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, the Brazilian economy experienced an “economic miracle” of annual double-digit growth in GDP.

69 Id. at 48.

70 Id. at 48-49.

71 LEONEL ITAUSSU ALMEIDA MELLO, ARGENTINA E BRASIL: A BALANCA DE PODER NO CONE SUL 148 (1996).

72 The Brazilian action, in effect, nullified a treaty that the country had signed in 1969 with Argentina, Bolivia, Paraguay and Uruguay to promote the harmonious and physical integration of the five signatory states through, among other things, the equitable use of the region’s water systems.

73 For example, in 1971 the Brazilians financially underwrote Hugo Banzer's overthrow of the leftist General Juan José Torres in Bolivia, providing Banzer with air support and stationing troops at the border in the Brazilian State of Mato Grosso in the event their intervention in Bolivia was required. MONIZ BANDEIRA, supra note 50, at 54. Similarly, Brazilian troops were stationed on the Uruguayan border in 1971 poised to invade the country in the event the leftist Frente Amplio won the presidential elections of that year. Id. at 54-55. Following the coup d’etat in 1973, Brazil provided the new Uruguayan military government with generous financial credits, intelligence help, training in torture techniques, and VW buses for the security forces. Id. at 55. Brazil played a similar role in Chile after the 1973 military overthrow of democratically elected Salvador Allende.

74 Id. at 60. This explains the widespread sense of alarm generated by a December 1971 remark made by then U.S. President Richard M. Nixon during a welcoming ceremony at the White House for Brazilian President General Emilio Medici "that as Brazil goes so will the rest of the Latin American continent”. See, e.g., Joseph Novitski, Medici Denies Brazil is Seeking Domination over Latin America, N.Y. TIMES, Dec. 31, 1971, at 3.

75Wayne A. Selcher, Current Dynamics and Future Prospects of Brazil’s Relations with Latin America: Toward a Pattern of Bilateral Cooperation, J. OF INTER-AM. STUD. & WORLD AFF., Summer 1986, at 67, 68-69. By the late 1970’s and until 1982, South American markets had become the most dynamic in the world for Brazilian exports, representing 18.1% and 19.3% of total Brazilian exports for 1980 and 1981 respectively (shares larger than those absorbed by the United States). Id. at 81.

76 By this treaty the signatory states pledged themselves to promote the rational occupation and economic development of the Amazon region as well as to encourage the economic and social integration of the eight signatory states. Treaty for Amazonian Cooperation, July 3, 1978, 1202 U.N.T.S. 71.

77 Los Vínculos de Brasil con el Grupo Andino, LA NACIÓN, Oct. 17, 1979, at 2.

78 As a result of the Tripartite Agreement, Brazil agreed to reduce its original plan from twenty to eighteen turbines and to regulate water flows through the Itaipú dam throughout the year so as not to affect river traffic and the planned Argentine-Paraguayan dam at Corpus further downstream. Acordo de Itaipu Reative Antigos Projetos, JORNAL DO BRASIL, Oct. 19, 1979, at 23.

79 ITAUSSU ALMEIDA MELLO, supra note 71, at 150.

80 Id.

81 Meta é Criar Bases Politicas e Juridicas, JORNAL DO BRASIL, May 18, 1980, at 22. In particular, both countries agreed to share hydroelectric power obtained from the Uruguay River and its tributaries, interconnect the two countries' electrical systems, build a military plane together, eliminate effects of double taxation, and construct a second bridge to link the two nations by road at Iguaçu,. Argentina also agreed to provide Brazil with excess natural gas production and uranium. MONIZ BANDEIRA, supra note 50, at 67.

82 Delfim Anuncia Criação de Comissão Bilateral, JORNAL DO BRASIL, May 16, 1980, at 4. In August of 1980, General Videla travelled to Brasilia where he and Figueiredo signed seven additional agreements, including additional protocols to the nuclear pact of the previous May.

83 FRANCISCO THOMPSON FLORES NETO, INTEGRACÃO E COOPERACÃO BRASIL-ARGENTINA 5 (1991); Meta é Criar Bases Politicas e Juridicas, supra note 81, at 22.

84 The Argentine leaders apparently believed that by tying themselves closer to the major power in the Western Hemisphere, the United States, through such things as training the Nicaraguan contras, Argentina would somehow be able to regain her former status as a regional power. Ironically, this had been the Brazilian strategy of the 1960s and early 1970s but had already been abandoned as a failure.

85Wayne A. Selcher, Brazilian-Argentine Relations in the 1980s: From Wary Rivalry to Friendly Competition, 27 J. OF INTERAM. STUDIES & WORLD AFF., Summer 1985, at 25, 30.

86Id. At 35.

87 Oscar Camilion, La Evaluación Argentina, in ARGENTINA-BRASIL: EL LARGO CAMINO DE LA INTEGRACIÓN 155, 157 (Mónica Hirst ed., 1988).

88 See, e.g., THOMAS ANDREW O’KEEFE, LATIN AMERICAN TRADE AGREEMENTS 4-2 (2004) [hereinafter O’KEEFE, LATIN AMERICAN TRADE AGREEMENTS].

89 Id.

90 Id. at 4-5.

91 Id. at 5-10.1 to 5-17.

92 Neantro Saavedra-Rivano, A Integração Econômica Brasileira-Argentina no Contexto da Cooperação Econômica Sul-Sul, in BRASIL-ARGENTINA-URUGUAI: A INTEGRACÃO EM DEBATE 69, 73 (Renato Baumann & Juan Carlos Lerda, eds., 1987).

93 Id.

94 see, e.g., O’KEEFE, LATIN AMERICAN TRADE AGREENENTS, supra note 88, at 4-2.

95 Id.

96 Tulio Vigevani & João Paulo Viega, MECOSUL e os Interesses Políticos e Socias, 5 SAO PAULO EM PERSPECTIVA, July.Sept. 1991, 44-46. Throughout the late 1980’s, as the PICAB was implemented, trade between Argentina and Brazil grew significantly over historic levels.

97 See Hugo Martinez, Convênio com Brasil é Básico para Argentina, O ESTADO DE SAO PAULO, Nov. 29, 1988, at 4; Hugo Martinez, Trabalho se Soprepõe às Formalidades, O ESTADO DE SAO PAULO, Dec. 1, 1988, at 5.

98 A retired Brazilian vice-admiral attending a Buenos Aires symposium sponsored by the general staffs of the Argentine and Brazilian Armed Forces in April 1987 credited the PICAB with giving each country’s military a “new horizon”. At this same symposium, the construction of a binational nuclear submarine was proposed. See, Military Affairs: Proposals for Closer Ties with Argentina, LATIN AM. WKLY REP., Apr. 23, 1987, at 9.

99 Maurício Cardoso, Brasil e Argentina Dão Passo Final na Integracão Econômica, JORNAL DO BRASIL, Nov. 27, 1988, at 19.

100 See O’KEEFE, LATIN AMERICAN TRADE AGREEMENTS, supra note 88, at 4-1.

101 Id. at 4-1, 4-2.

102 ALADI, based in Montevideo, Uruguay, replaced the unsuccessful Latin American Free Trade Area (“ALALC”) effort in 1980. It encourages economic integration among its membership: all the Spanish speaking countries of South America plus Brazil and Mexico. For more detailed information about ALALC and ALADI see O’KEEFE, LATIN AMERICAN TRADE AGREEMENTS, supra note 88.

103 Id. at 4-1.

104 Id.

105 Id.

106 Id. at 4-1 to 4-2.

107 Id. at 5-1.

108 Id.

109 Id. at 5-1 to 5-5.

110 Id. at 5-5.

111 See Thomas Andrew O’Keefe, A Resurgent MERCOSUR: Confronting Economic Crises and Negotiating Trade Agreements, 60 NORTH-SOUTH AGENDA PAPERS 4-5 (Jan. 2003) [hereinafter O’Keefe, A Resurgent MERCOSUR], available at http://www.miami.edu/nsc/publications/pub-ap-pdf/60AP.pdf

112 Id. at 5-6.

113 Id. at 5.

114 For a more detailed description of the recent trials and tribulations facing MERCOSUR and how they have gradually been overcome, see O’Keefe, A Resurgent MERCOSUR, supra note 111.

115 Id. at 3.

116 Hector Tobar, Argentina’s Leader Takes Office Amid High Hopes, CHI. TRIB., May 26, 2003, at A4; Dignitaries Start to Arrive for President’s Inauguration, ORLANDO SENTINEL, Aug. 15, 2003, at A17.

117 O’KEEFE, LATIN AMERICAN TRADE AGREEMENTS, supra note 88, at 15-14.

118 Id.

119 Id.

120 See, e.g., Pedro da Motta Veiga, Brazil in MERCOSUR: Reciprocal Influence in MERCOSUR: REGIONAL INTEGRATION, WORLD MARKETS 25, 30 (Riordan Roett, ed., 1999). Da Motta Veiga emphasizes that MERCOSUR was responsible for the most important changes of the 1990’s to Brazilian foreign trade patterns, by favoring export of goods with a higher degree of technological innovation. Id. at 30-31. This encouraged small and medium-sized firms in Brazil to export for the first time. Id. at 30. MERCOSUR also has encouraged increased Brazilian foreign investment in the subregion, thereby playing an important role in the internationalization of Brazilian firms. Id. at 31.

121 Monica Hirst, Mercosur’s Complex Political Agenda in MERCOSUR: REGIONAL INTEGRATION, WORLD MARKETS, supra note 120, at 35, 43. Hirst notes that besides “these initiatives at the local and federal levels, cross-border interaction has been intense among business sectors, social organizations, and political elites, and inter-provincial networking is [a reality] between the southern states of Brazil and the northern provinces of Argentina. Id

122 In his seminal work on the subject matter, Bela Balassa identified five basic forms that economic integration can take. BELA BALASSA, THE THEORY OF ECONOMIC INTEGRATION 2 (1962). The first and least complicated consists of the creation of a free trade area in which tariffs and quantitative restrictions are eliminated on trade between participating countries, although each nation retains its tariff structure as against non-participants. Id. A customs union adds to the free trade area the equalization of tariffs by participating states against imports from non-members (i.e., the implementation of a Common External Tariff or CET). Id. A common market includes free trade in commodities among participating states, a CET, as well as the elimination of restrictions on the free movement of factors of production (i.e., labor and capital) among the member states. Id. An economic union adds to the common market framework some degree of harmonization of national economic policies in order to remove discrimination that was due to previous disparities among participating states in these policies (e.g., the creation of a Central Bank with some supranational powers). Id. “Finally, total economic integration presupposes the unification of monetary, fiscal, social, and counter-cyclical policies and requires the [establishment] of a supranational authority whose decisions are binding for the member states” (i.e., in essence the establishment of a political federation). Id.

123JOSEF M. VAN BRABANT, ECONOMIC INTEGRATION IN EASTERN EUROPE: A HANDBOOK 12 (1989).

124 Id.

125 Stirk & Weigall, supra note 7, at 36.

126 VAN BRABANT, supra note 123, at 11.

127 Id. at 63-69.

128 Id. at 69. Romania’s opposition appears to have been premised, in part, on a long tradition of protectionism dating back to the nineteenth century, as well as a feeling that an ambitious integration project that included ceding sovereignty to a supranational body was incompatible with the concept of a socialist state and the need to foster the development of an industrial proletariat through the promotion of heavy industry. Id.

129 Stefan Wagstyl, Kosovo Frustrations Simmering as Inter-Ethnic Tensions Remain Unresolved, FIN. TIMES, July 27, 2004, at 6.

130 See, e.g., The Regatta Sets Sail, ECONOMIST, June 28, 2003, at 52-53; Something Rotten, ECONOMIST, July 19, 2003, at 40.

131 William P. Avery & James D. Cochrane, Innovation in Latin American Regionalism: The Andean Common Market, 27 INT’L ORG. 181, 207 (1973). Three schools of political theories of economic integration exist. “the federalist approach [now largely discredited], which emphasizes the role of institutions; the transactional approach [considered outdated]which stresses transactions between people; and the neo-functionalist approach which focuses on the ways in which supranational institutions emerge from a convergence of interests of various significant groups in society. “ ALICIA PUYANA DE PALACIOS, ECONOMIC INTEGRATION AMONG UNEQUAL PARTNERS: THE CASE OF THE ANDEAN GROUP xxi (1982).

132 Avery & Cochrane, supra note 131, at 207. This view of relative power-size homogeneity has been attacked by others who argue that “core areas” within a proposed union can provide a centripetal force or locomotive effect that initially helps push the integration process forward.

133 Id. at 209.

134 Id. at 207.

135 Id. at 214. The fact that the advantages and drawbacks of an integration process can be openly debated should mean that any final decision to proceed with such a project has strong societal support that will help overcome temporary setbacks that may appear on the road to economic integration.

136 Id. at 207. “In general, the greater the [complementation of opinion among] elites with effective power over economic policy as reflected in similar statements and policies toward the most salient political-economic issues in their region, the better the conditions for positive or integrative response.” Joseph S. Nye, Comparing Common Markets: A Revised Neo-Functionalist Model, 24 INT’L ORG.796, 817 (1970). For example, by the early 1990’s, there was widespread support for closely integrating the Argentine and Brazilian economies among politicians, business executives, academics and other opinion makers in both societies, thereby facilitating the creation of MERCOSUR. On the other hand, there was little consensus in Central America as to the wisdom of creating a Common Market during the 1960’s, contributing, in part, to the eventual stagnation of that integration process. Similarly, large numbers of the opinion makers in certain EU countries have resisted the idea of surrendering macroeconomic policy making to the European Central Bank, hence the refusal by Denmark, Sweden, and the United Kingdom to adopt the euro as their monetary unit.

137 Avery & Cochrane, supra note 131, at 207. High levels of perceived dependence, whether the result of threats from the external world, exports to predominantly one country, or high reliance on external moral and physical aid, is thought to reinforce the desire for unity in order to “get out from under” the domination of the metropolitan power. Mario Barrera & Ernest B. Haas, The Operationalization of Some Variables Related to Regional Integration: A Research Note, 23 INT’L ORG. 150, 152 (1969).

138 Joseph S. Nye, Patterns and Catalysts in Regional Integration, 19 INT’L ORG. 870, 882 (1965). For example, Nye points out that “European integration was helped by its initiation in an environment in which Europe had (as a result of [WW II]) undergone a drastic change from an autonomous actor to pawn in a bipolar power struggle. Id. at 883.

139 CENT. INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, THE WORLD FACTBOOK, “Economy” Category for Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Macedonia, Romania, Serbia & Montenegro (2003), available at http://www.frogcement.com/fbook3/.

140 Id.

141 Id.

142 Id.

143 Martin Wolf, Europe Risks Destruction to Widen Peace and Prosperity, FIN. TIMES, Dec. 11, 2002, at 23.

144 See, e.g., CENT. INTELLIGENCE AGENCY, THE WORLD FACT BOOK (2004), available at http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/ (citing the “economy” category for Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia & Montenegro).

145 See tbl. 1.

146 See, e.g., O’KEEFE, LATIN AMERICAN TRADE AGREEMENTS, supra note 88, at 1-4.

147 Id.

148 Id. at 15-14.

149 K.P.E. LASOK & D. LASOK, THE LAW AND INSTITUTIONS OF THE EUROPEAN UNION 9-10 (7th ed. 2001).

150 Katinka Barysch, E.U. Enlargement: How to Reap the Benefits, ECON. TRENDS, June 2004, at 28, available at http://www.cer.org.uk/pdf/barysch_economictrends_june%2004.pdf

151 Although it has increased the negotiating power of the MERCOSUR countries (particularly the three smaller members) in the FTAA negotiations, U.S. negotiators have now also come to appreciate the bloc as facilitating negotiation logistics since at least four of the thirty-four countries have already worked things out among themselves before they sit down at the negotiating table.